Back in May, he risked a six-month prison sentence or $15 fine for refusing to download the app. Ghosh didn’t care: He had bigger concerns about the future use of his data.

“I am not sure how the government will use my data. If they want, they can do surveillance on me forever through location-tracking on the app,” said Ghosh.

The Indian government maintains that most personal and location data of users is ultimately deleted, but critics say India’s lack of data protection laws exposes millions of people to potential privacy breaches. They also fear that personal information could be sold by the government to private companies, or even used for surveillance beyond Covid-19 concerns.

Millions of users

The Aarogya Setu app was developed by the National Informatics Centre, an ICT and e-governance body under the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, in collaboration with voluntary technical experts from private industry and academia.

Unlike many other countries’ contact tracing apps, Aarogya Setu uses Bluetooth and GPS location data to monitor the app users’ movement and proximity to other people.

Users are asked to input their name, phone number, age, gender, profession and the countries they have visited in the past 30 days, as well as prior health conditions and a self-assessment about any Covid-19-related symptoms.

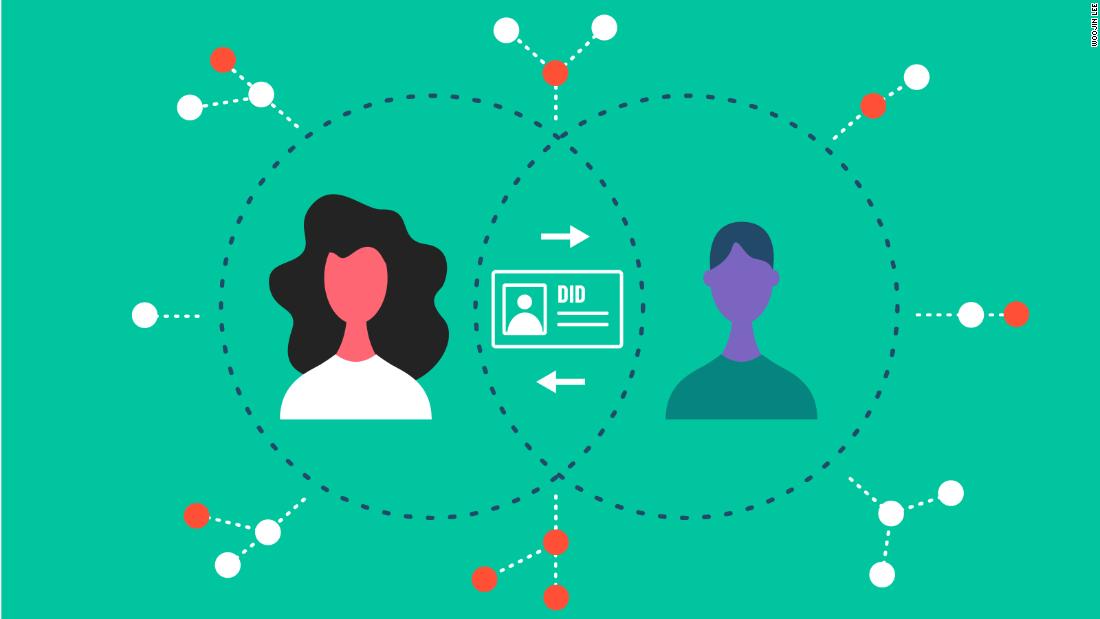

A unique digital ID (DiD) is generated for each user, which is used for all future app-related transactions. Through GPS, the app records each users’ location every 15 minutes.

When two registered users come within Bluetooth range of each other, their apps automatically exchange DiDs and record the time and location. If one of the users tests positive for Covid-19, the information is uploaded from their phone onto the Indian government’s server and used for contact tracing.

As of June 1st, Aarogya Setu had identified 200,000 at-risk people and 3,500 Covid-19 hotspots, according to lead developer Lalitesh Katragadda, the founder of Indihood, a private firm that builds crowdsourcing population-scale platforms, and one of the private industry volunteers who worked with government agencies on the app.

“We have a 24% efficacy rate, that is, 24% of all the people estimated to have Covid-19 because of the app have tested positive,” said Katragadda. This means that only about 1 in 4 people advised by the app to get a test actually tests positive.

Subhashis Bannerjee, professor of computer science and engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi, said the combination of Bluetooth and GPS location would likely return a higher rate of false positives and false negatives. For example, GPS is often unavailable or unreliable indoors, and Bluetooth overestimates the risks in large open spaces, across walls and floors, which radio waves can penetrate but the virus cannot.

Government safeguards

The Indian government states that enough privacy and protection parameters have been built in to ensure permanent deletion of the app’s data.

“All contact tracing and location data on the phone is deleted on a rolling 30-day cycle. The same data on the server is deleted 45 days from the upload unless you test positive. In which case all contact tracing and location information is deleted after 60 days after being declared cured,” said Abhishek Singh, CEO of MyGov at India’s IT ministry.

“There is no way to check and verify whether the complete destruction of data has taken place and if any third parties with whom the data is shared has also destroyed it,” said Apar Gupta, a lawyer and executive director of the IFF.

In response to calls for more transparency, the Indian government opened up the app’s source code on May 27 and announced a bug bounty program to incentivize software experts to find security vulnerabilities in the app, to rectify lapses, if any.

On June 1, Singh of MyGov, said the government planned to release the server code in a few weeks.

However, Katragadda said that even with the server code, access to information on data sharing would be restricted.

“It will never be possible to see exactly with whom the data is shared because for that we will have to open source the entire government,” he said.

No data protection laws

The Personal Data Protection Bill imposes limits on how residents’ personal data is used, processed and stored. If passed, the bill would also establish a new regulatory body — the Data Protection Authority (DPA) — to monitor compliance. Critics say the bill is flawed for a number of reasons, including that it allows the government to exempt its departments from the legislation on the basis of national security.

But right now, there are few safeguards for data in India.

“No legislative framework means no official level of accountability. So, if any data mishap happens, there will be no penalty, there will be no safeguards,” said Gupta.

“India has made a strategy to sell citizen data and is thus making it a commodity by claiming ownership over Indians’ personal data, which is against Indians’ fundamental right to privacy,” said Kodali, the public interest technologist.

Last year, the Modi government sold citizens’ vehicular registration and driving license data to 87 private companies for 65 crore rupees (approximately $8.7 million) without citizens’ consent. This caused a backlash with the opposition party questioning the motives of the government and the price of the sale in parliament.

Despite the government’s assurances that all Aarogya Setu data will be deleted, Katragadda told CNN Business that some information from the app will be automatically transferred to the National Health Stack (NHS). The NHS is a cloud-based health registry, currently under development, that will include citizens’ medical history, insurance coverage and claims.

“Any residual data from the Aarogya Setu app will automatically move into the National Health Stack within the consent architecture, as soon as the health stack comes into effect,” said Katragadda.

Residual data means any data that’s still on the govt server at the time the NHS becomes active. That includes location, health and personal data that has been downloaded to the server but hasn’t yet been deleted in the timeframes laid out by the government, Katragadda said.

No date has been set for the release of the NHS, but Gupta of IFF worries, again, that there’s no legal framework to protect the data.

“Even though it is repeatedly stated that consent will be the basis of the information sharing, it’s important to note that in both the Aarogya Setu app and NHS, consent is baked into the architecture which is a technical framework rather than a clear source of legal authority.”

Ticket to move

Like other countries that have introduced a contact tracing app, India says the technology is vital to stop the virus from spreading. As of June 22, the country had confirmed more than 410,000 cases and 13,254 deaths.

Citizens and activists also fear function creep of the app, meaning that information obtained through the app could be linked to other services.

“In the past we have seen that technology interventions by this government such as the Aadhar program, which was initially built to ensure that everyone has a digital identity, became a pervasive system, said Gupta.

“Initially built for the purposes of accessing government benefits and subsidies, it was soon mandated for opening bank accounts, availing mobile numbers and going about your business.”

However, in 2018 a journalist discovered a security breach which disclosed citizens’ personal details. The government introduced new security measures, but the scandal eroded trust in its ability to keep data safe.

Before easing off its compulsory download order, India was the only democratic country that made it mandatory for millions of citizens to download the app. The only other countries to impose a similar order were Turkey and China. Campaigners say that alone is cause for concern.

“When it comes to technology and public use, the world’s largest democracy is drawing from China’s playbook — using national security or a public health crisis to build a digital model of data-gathering, oversight and surveillance,” said Vidushi Marda, a lawyer working on emerging technology and human rights.

“I would say these kinds of complex technical architectures are not happening in a collective fashion in India, but there is a danger they will be built in through platforms like the National Health Stack,” said Gupta.