They weren’t committing a crime: they were carrying a caged tiger.

Two days earlier, the men realized a deer trap they had set 400 yards (365 meters) from their village had gone missing. They followed tracks etched in the dirt where it had been dragged to a pit — inside, they discovered a wounded tiger, the jaws of the metal snare biting into its leg.

Police sent the tiger to a Hong Kong amusement park, where it died shortly after. A policeman became the “proud possessor of the skin,” according to a later news report.

“That story makes you wonder how many tigers were being carried around by locals that we never heard about,” says John Saeki, a journalist who is researching a book about tigers in Hong Kong.

In the early 1900s, zoologists — and the public — were skeptical that wild tigers existed in Hong Kong, despite repeated incidents. Saeki has found hundreds of mentions of tiger sightings and big cat encounters in local newspapers, from the 1920s to as recently as the 1960s — although some might have been sightings of the same tiger, while others were not verified to be more than a rumor.

So how could tiger sightings be real when big cats didn’t live in Hong Kong?

Saeki explains that political turmoil in mainland China in the first half of the 20th century made food harder to find for the South China tiger.

About 20,000 of the diminutive cats, the smallest of the tiger species, roamed the mostly rural mountains of southern China during that period. Some would slink over the border to feast on farmers’ cattle and boar in Hong Kong, before slipping back over the hills to the north — occasionally feasting on a human, rather than an animal.

The South China tiger

The tiger is a potent symbol in Chinese culture. In traditional Chinese medicine, tiger-penis soup has for centuries been consumed by men to increase sexual virility. Tiger-bone wine is believed to cure rheumatism, weakness, or paralysis. And tiger whiskers were once used for toothaches, eyeballs for epilepsy — the list goes on.

The white tiger is one of the four sacred animals of the Chinese constellation. And those born in the year of the tiger are thought to be brave, strong, and sympathetic.

But on a practical level, these majestic big cats have for centuries preyed on humans in China.

More than 10,000 people were killed or injured by tigers in four provinces of South China — Fujian, Jiangxi, Hunan, and Guangdong — between the years 48 A.D. to 1953, according to gazetteer records in the Ancient Books Collection at Fujian Normal University, analyzed by Chris Coggins in his 2003 book “The Tiger and the Pangolin: Nature, Culture and Conservation in China.”

He says that figure is conservative because 395 records did not specify the numbers of casualties — just that at least one attack had occurred. Tiger encounters featured more regularly in records than those by Asiatic black bears, wolves, red dogs, or wild boar, Coggins writes, and were predominantly South China tigers. Small numbers of Siberian and Bengal tigers still live in other pockets of China, but it was the South China tiger that encountered humans south of the Yangtze River.

In the early 20th century, when American Methodist Harry Caldwell turned up in southern China on a mission to spread Christianity, he chanced on a near-foolproof way to convert villagers into Christians — he taught them how to kill tigers. In his memoir “Blue Tiger,” Caldwell describes how, in April 1910, he shot dead a big cat that had just killed a 16-year-old Chinese boy. “The killing of that beast turned almost an entire village Christian,” he wrote. The Chinese, as he tells it, were fascinated by his American gun.

Any God that made such a machine, he convinced them, was one they should worship.

In his book, Caldwell tells of villages under siege from big cats across southern China. Fuqing, a coastal community in Fujian province, was the heart of South China tiger country. In this village — which is now a city — Caldwell describes how every person bolted their gate at night, and protectively brought their precious cattle, pigs and water buffalo into the inner courtyards of their homes, petrified of nightly tiger attacks.

“Men tending their herds or walking along the trails disappeared, or were found mangled and half eaten. Crops were going untended; paralysis began to settle on the hills … People were afraid to stir from their houses,” wrote Henry’s son, John Caldwell, in a 1953 book about his father’s life.

Henry Caldwell boasted of killing nearly 50 of the South China tigers that had stalked a vast area south of the Yangtze River for centuries, as he pushed religion with his rifle.

Caldwell’s tiger hunting went unchecked, as did that of British trophy hunters such as William Lord Smith, who recounted his tales in the 1920 book “The Cave Tiger of China.”

When the Communist Party of China came to power in 1949, things didn’t get better, with Chairman Mao Zedong taking aim at animals deemed to be pests such as tigers, says Saeki. “There was a concerted campaign to wipe them out,” he adds.

Coggins writes that animals that attacked livestock, ate crops, or spread disease were seen as an obstacle to progress. “Large livestock predators, such as tigers (which have a colorful history of dining on people in southern China) and wolves, were attacked systematically. Animals that posed a threat to grain crops were trapped, shot, and poisoned by the thousands,” Coggins writes.

From the 1940s onwards, Saeki says, the number of tiger sightings in Hong Kong rocketed, as the big cats — which thought nothing of walking 20 miles (32 kilometers) in a day — trekked further afield to find food.

Tigers in Hong Kong

As the city urbanized throughout the 20th century, tiger storiesbecamea fanciful distraction from the tumult of two world wars, and then the huge influx of migrants who poured over the border from mainland China.

But two big cat tales, in particular, have lingered in the public imagination — perhaps because the stuffed bodies of both their protagonists have been displayed in the city.

The first story involves a tiger from 1915.

Then a villager died — and the police took their claims seriously.

Ernest Goucher, a 21-year-old police officer from Nottingham, England, was dispatched to investigate, along with his Indian colleague, Constable Ruttan Singh. The two were attacked by the huge tiger — Singh died immediately, while Groucher was taken to hospital, “terribly lacerated about the loins,” according to media reports. He died soon after.

When Assistant Superintendent of Police, Donald Burlingham, finally shot dead the animal on March 9, 1915, it measured just over 7 feet (2.2 meters) from the tip of its nose to the end of its tail, was about 3 feet (1 meter) high and its paws were 6 inches (15 centimeters) across. It weighed 288 pounds (131 kilograms).

When the dead cat was exhibited in Hong Kong City Hall the day after it had been shot, thousands of people lined up to see it. Today, its stuffed head is on display at the city’s Police Museum.

The other tale is of a big cat, whose skin hangs in the Tin Hau Temple in Stanley, on the belly of Hong Kong Island.

For weeks, it prowled the grounds at night, roaring at internees.

George Wright-Nooth, a prisoner at the camp, wrote in his diary: “Last night Langston and Dalziel, who were sleeping outside at the back of the bungalow, were woken up at about 5.00 a.m. by snarls and growls.”

“Langston … got up to have a look. He went to the edge of the garden and looked down the slope to the wire fence. There Dalziel saw him leap in the air and fly back into the boiler room shouting ‘There’s a tiger down there.'”

Within the camp, Wright-Nooth wrote, “none of the bungalows has any doors or windows” — the open camp was largely self-governed by the foreign prisoners, and fortified by high fences and soldiers with guns to prevent their escape.

Eventually, an Indian police officer shot the tiger. One of the internees, a butcher before the war, was taken out of the camp to skin the animal, which was then stuffed and displayedin the city.

“The meat was not wasted either,” Wright-Nooth wrote. “Some officials of the Hong Kong Race Club were recently given the rare treat of having a feast of tiger meat.

“The meat, which was as tender and delicious as beef, was from the tiger shot at Stanley.”

No chance today

In the post-war years, tiger sightings in Hong Kong became less frequent, with news reports in the late 1950s chronicling sightings that were never confirmed.

In 1965, a schoolgirl reported seeing a tiger on Tai Mo Shan, Hong Kong’s highest peak, but with no tell-tale paw prints, mangled cattle or photograph of the big cat, its existence was never confirmed.

The dwindling number of sightings was perhaps not unsurprising — tiger numbers in mainland China were dangerously low.

“They killed a lot of South China tigers in the 50s,” says Saeki. “Then by the 70s they realized they were about to lose one of the best, great species of China. And there was a kind of a panicked attempt to bring them back but it hasn’t really happened.”

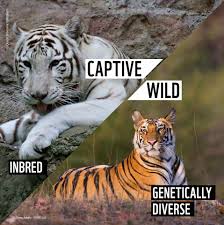

In 1977, the year after Mao’s death, the Chinese government outlawed the killing of tigers. In the following reform era, authorities hired specialists to investigate the status of the subspecies. Experts declared the South China tiger was on the verge of extinction, with just 30 to 50 of the animals believed to remain in wildly disparate pockets of their mountainous habitat — and therefore, unlikely to breed, writes Coggins.

“I saw a tiger in one facility in about 2014 that had severely deformed rear leg hind legs. It couldn’t even walk normally,” says Coggins. “I talked to one of the managers, who said it’s probably a genetic defect. So that project has not really gone forward.”

Instead, Beijing is putting more attention into its conservation efforts for the Siberian tiger — of which there are fewer than 500 left in the world, and which roam across the border from Russia, into China’s far northeast.

That tiger, experts agree, is unlikely to ever find a need to wander down to Hong Kong, where tiger sightings are now limited to the stuffed and skinned animals of a bygone species.